Discussion Topic

In this series I am looking at some classic science fiction stories and suggesting how they might be used as the basis for discussions in Computing (and related subjects) classes. The Computing Programme of Study in England gives plenty of scope for discussing the ramifications of developments in technology. The aims, in particular, include the following broad statements:

The national curriculum for computing aims to ensure that all pupils:

...

- can evaluate and apply information technology, including new or unfamiliar technologies, analytically to solve problems

- are responsible, competent, confident and creative users of information and communication technology

Spoiler alert: in order to discuss these stories, I have had to reveal the plot and the outcome. However, in each case I’ve provided a link to a book in which you can find the story, should you wish to read it first.

Time travel is a favourite theme of science fiction writers. I have often thought what a pity it is that time travel is unlikely to ever be possible. But perhaps we should be thankful for that…

We tend to fantasise about time travel as a way of changing the past, usually for the better. For example, what if someone could go back in time and kill Hitler, or even prevent him from being born?

This post is part of a new series on the theme of dystopian visions, in a relatively new section called Fiction of my Eclecticism newsletter.

Interestingly, a more acceptable version of this kind of speculation is the branch of study known as “alternative history”.

Of course, it’s based on the premise that the “correction” would improve matters. In the case of Hitler, such musing ignores the fact that all the elements of a situation in which such a demagogue could take power were already in place. If Hitler had never been born, it’s arguable that someone even worse may have come to power instead.

Leaving alternative history aside, what if an amazing technology like time travel were used purely and simply as a form of punishment? Not to make life better in the present, but to ensure that anyone found guilty of treason is severely punished in one of the most awful ways imaginable. In the story called My Object All Sublime, Poul Anderson explores this idea. The punishment described has profound moral implications that extend far beyond the person being punished.

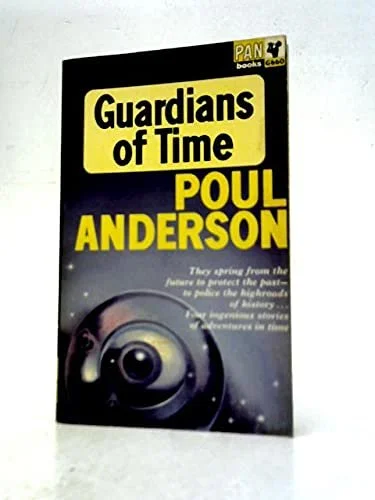

Poul Anderson first came to my attention through his book Guardians of Time.

Click here to see this book on Amazon (affiliate link)

This is a collection of four short stories centred on the activities of an organisation called Time Patrol, which sets out to correct anolalies in the time stream. Like a lot of science fiction, it’s not great literature, but it is tremendously enjoyable. And, of course, is predicated on the assumptions that such mistakes can be identified1, and that the corrections will work, and that the motivation of organisations like the Time Patrol are wholly benign.

Moving on to My Object All Sublime, which you can find in The Giant Book of SF Stories, I won’t spoil the story and the surprise ending, but it does raise issues which apply to other forms of technological inventions as well. Namely:

Our technological abilities seem to me to advance a lot faster than our ability to handle and control them, as opposed to them controlling us. Would you agree?

Are we in danger of losing touch with values like kindness and spirituality?

And if the answer to either of these points is “yes”, what should, or perhaps more realistically could, be done about them?

I suppose a legitimate question is: why bother to discuss this in the first place, given that time travel is impossible anyway? Isn’t it a bit like discussing how many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

To my mind, the impossibility of time travel makes it easier to discuss moral issues arising, or that could and should be anticipated, from our inventions.

This article first appeared in my Eclecticism newsletter, here. Go there if you'd like to leave a comment.