UPDATED! This is an updated version of an article originally published on 15 March 2012. The terminology has been updated, and a now-defunct link removed.

Terry thinking of practical solutions -- by Terry Freedman

“But what do you actually have to do?”

“You have to implement this solution.”

“Yes, but what do I do?”

“You have to implement this solution.”

“How? Who do I have to speak to? What should I say?”

I seem to have these conversations all the time. It’s fine being a visionary, but somewhere along the line someone has to actually do something.

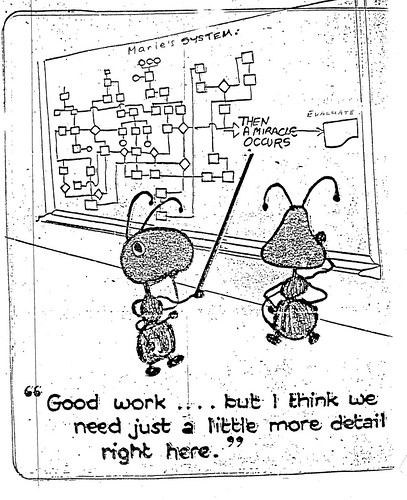

I don't know the author of this cartoon. If you have any information about its source, please let me know so that I may accredit it properly. Thank you.

The interesting thing, though, is that nobody likes a pragmatist. Or, rather, they do, except when it’s they who are being pressured. That’s not a criticism, only an observation. I’m as guilty of that behaviour as anyone else: I hate it when someone says, “Yes, but…”. What right do they have to put practical issues before such a wonderful vision, before my brilliant idea?

I think education technology especially lends itself to flights of fancy that come adrift from their moorings (if they were ever attached to their moorings in the first place). We get carried away with the possibilities, but forget the down-to-earth stuff. For example, how many interactive whiteboard-equipped classrooms have a lockable cupboard in which the whiteboard pens and other accessories may be stored safely? Or, to take another example, how come many new schools are built as open plan areas, and end up having walls put in afterwards in order to block out the noise from one class “room” to another? Anyone contemplating having such a design implemented needs simply to find some people who were educated in Britain in the 1970s, when open plan was all the rage, and ask them how they found it. Open plan may look great on paper, and may lend itself to inter-class collaboration (although I’m not quite sure how: is going through a door really that difficult, especially if wheelchair users are taken into account?), but on a real, down-to-earth basis, the noise contamination can completely spoil it. But why let a practical matter like that get in the way of a good idea? A good idea that, we should remember, almost certainly won’t affect the architect or their own kids!

Going back to the opening paragraph of this article, it’s good to have a vision for education technology, but you also need a strategy whereby the vision will come into being. It’s no good hoping for a miracle. You’ll make yourself unpopular by asking questions like “what?”, “How?”, “Who”; but if you really believe in the vision, what choice do you have?

For more articles about education, and literature, writing and life in general, please visit my newsletter, Eclecticism.