The following article was written with the then new English Computing curriculum in mind. However, it has some useful points about planning which I think are still relevant today, and in a wider context.

At first sight, it seems bizarre that despite the fact that many teachers urgently need professional development, and time, in order to be ready to teach Computing in September, headteachers are not always allowing them to attend courses during school time. A business planning approach by ICT leaders in school could help.

You may think that a business plan is not relevant to you because you’re not running a business. But actually, many of the things that a business has to do, like marketing and budgeting – and planning – are what you do have to do in one form or another. All a business plan is is a statement of where you would like to be at a certain point in the future, and what steps you need to take in order to get there.

Before talking about business planning, though, I’d just like to explain how this post has arisen. What’s the story behind it?

The story

Planning is essential. Photo from Stencil. Licence: CC0

I chaired and presented at a conference about implementing the new Computing curriculum, run by Understanding Modern Government. Featuring a great line up, including Ian Livingstone, Peter Marshman, Neil Rickus, Alan Mackenzie and Drew Buddie, the conference was intended to convey the message that the Computing curriculum can be engaging, challenging (in a good way!) and, above all, doable. I think we largely succeeded, and the comments we received bears this out:

“fantastic course, I am taking back loads of ideas to implement”

“lots of information that can be used/tried – good to have enthusiastic speakers”

“lots of ideas given – food for thought”

“well delivered course, very informative”

“comprehensive, relevant and using current information to present new computing curriculum in succinct chunks”

“many inspiring speakers with great ideas for implementing the new computing curriculum”

With regard to that last aim, of helping people to see that implementing the new arrangements was not an impossible task, Neil and I ran a workshop towards the end of the day in which we took delegates through action planning. One of the outcomes of this was that delegates realised, or had confirmed, that they would need more time to get to grips with it all. For example, they would need time and space just to look at the plethora of resources that speakers recommended throughout the day. The issue arose: how do we make our headteacher realise we need more time? Hence this article.

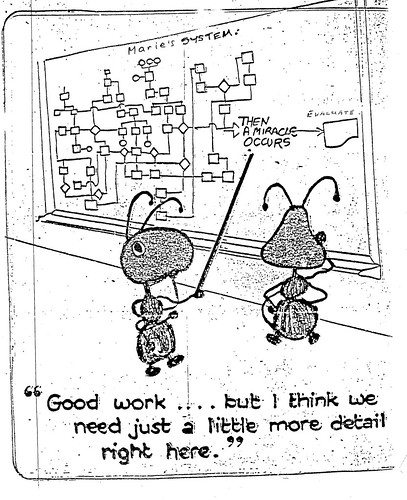

A business plan doesn’t have to be an in-depth, week by week, list of fully-costed actions – you're not applying for a bank loan! But it does need to contain rather more detail than this:

I’d recommend the following outline plan to share with your headteacher, and I’d aim to make it no longer than a side of A4 if you can. I’d also strongly recommend drawing it up with other members of your team, if you have one.

1. A statement of what needs to be achieved, and what it means

It is possible that headteachers don’t always fully understand the change that may be required. A Head of ICT told me she thought it was like asking a teacher of French to teach Russian from September. We were supposed to be doing a lot of this programming stuff anyway. As I reminded a group of teachers at the conference I mentioned a moment ago, it’s been on the National Curriculum since the very beginning, in 1989. Nevertheless, Ofsted consistently found that some parts of the old ICT Programme of Study, such as data logging and programming, were honoured more in the breach than the observance. In short, some ICT teachers do not have the requisite subject knowledge, and many schools will need to look at, and either tweak, or radically overhaul, their current scheme of work.

Don’t forget that it’s not just the subject knowledge but also your assessment methodology that needs to be worked out. You also need to know what resources you will need, and how much budget you will need in order to buy them.

And of course you will need to think about what technical support you need in order to offer the new curriculum. For example, do you need to negotiate with your technical support team to have a closed-off section of the school network in which students can create and run their programs?

2. A timescale

The new curriculum has to be taught from September. I don’t wish to speak for Ofsted or any other form of officialdom, but I should imagine some allowances will be made if you don’t have every single thing in place come September 1st. However, you need some things in place, like a scheme of work, the first unit or two, and the subject knowledge and resources to teach them, and a way of assessing pupils’ knowledge.

3. Professional development

What will arise from the foregoing is a good idea of what professional development you will need, and of what kinds, in order to reach a particular minimum starting point in September. For example, you may decide that you, or a member of your team, needs to go on a programming course. You may decide that you need to go on a course such one I run called New Assessment in ICT (which covers the new Computing Programme of Study) or Differentiation in Computing, or a course specifically about implementing the Computing curriculum in a secondary school, say.

(For some further ideas about courses, check out the list of providers in 9 Computing course providers to explore.)

And as likely as not, you will identify the need for a block of time in which you, and possibly a few colleagues too, look in some depth at the various resources and advice available. You will – or should – wish to meet with colleagues in the local primary schools if you are in a secondary school, or your local secondary school, if you are in a primary school, as I explained in 11 Reasons to collaborate with other schools in implementing the new Computing Programme of Study.

4. The outcome

What you should end up with is an outline plan that will convey information such as:

In order to have things in place by September to take us through the first half term, we will need to have done the following:

One day course on X in April

One “away day” for the ICT/Computing team in May

and so on.

You may find it helpful to set this out graphically instead.

5. Risk analysis

You may think that you will never be granted the time that you need, and you may well be right. However, you need to set out very clearly what the risks are of not having the time and support you have identified that you need.

For example, if you don’t have enough subject expertise, you will immediately make it less likely that the ICT/Computing provision in your school will be judged by Ofsted as “outstanding”. More importantly, you will find it more challenging to set appropriate work for your pupils, ie work that helps them progress beyond their current comfort zone. You will find it hard to assess pupils, and therefore to advise them on, and support them in, their next steps. Peer collaboration is all very well, but you still have to know enough about the subject to be able to group pupils in the most educationally useful way.

Another risk could well be that good teachers decide it’s time to go. I’ve heard of two cases where this has happened, because the teachers concerned didn’t have the confidence to learn how to teach computer programming etc.

A simple but effective approach to risk assessment is set out in an article called, perhaps not surprisingly, Risk Assessment.

Conclusion

A simple business plan such as the one suggested will be helpful in three ways:

It will help you to see what you need to achieve by September, and what you need to achieve, by when, in order to get there.

It will enable you to explain to your headteacher what needs to happen and, crucially, the risks of its not happening.

Finally, if the worst comes to the worst and you are not granted the time you think you need, and Computing in your school ends up not being as good as it might be because some of the things you were afraid might happen do happen (such as critical staff leaving), at least you will be able to remind the headteacher, as he or she is demanding to know why things aren’t great, that you did present an outline plan that included all the risks.

This isn’t as entirely as defensive or as negative as it may sound. When I was a manager of quite a large team, I had to explain to some of my staff that if they gave me their honest and expert assessment of what needed to be done in order to achieve or circumvent a particular situation, I could take a managerial decision about it. But I’d be pretty upset if, in the interests of not being the bearer of bad news, they didn’t inform me of all the facts in the first place. By presenting to your headteacher a business plan that includes a risk assessment, you provide him or her with the information they require to properly judge your case on its merits, and weigh your needs up in the context of the needs and resources of the whole school.

Related articles

- 9 Computing course providers to explore (ictineducation.org)