Help to bring education technology alive by introducing a letter from Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage.

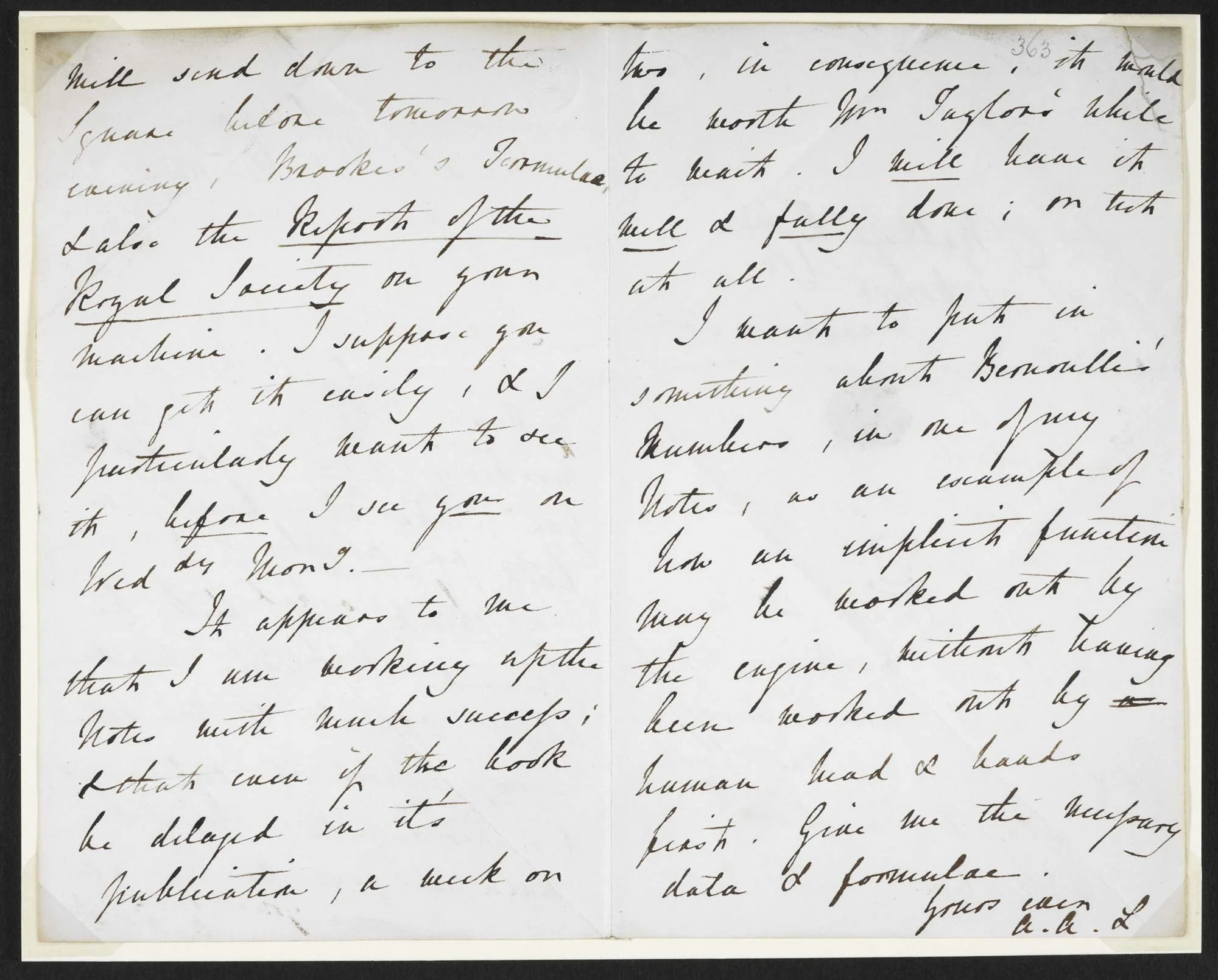

Letter from Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage. From the British Library. Licence: Public Domain

An education technology journey

You enter the British Library in London, go through security, climb up the steps, and then turn left. You're now in the Treasures Gallery. Stop! Look to your right. There, separated from you by only a pane of glass, is a letter sent by Ada Lovelace to Charles Babbage in 1843.

And the connection with education technology is...?

As the British Library puts it:

This letter from Lovelace to Babbage proposes an example of a calculation that ‘may be worked out by the engine without having been worked out by human head and hands first’. It is the first time that the principle of the computer program had been set out in writing.

That's what makes so exciting, so awe-inspiring. Babbage had built a "difference engine", a precursor to the calculator. He proposed a more general machine, known as the "analytical engine". He was without doubt a visionary -- modern computers are based on the same principles as the analytical engine. However, it was Ada Lovelace who first realised that such a machine could be used for much more than solving mathematical equations, and that it could, in effect, run itself.

I wrote in an article I wrote for a company blog recently that Lovelace was a woman born a century before her time. I don't think this is an exaggeration.

Introducing Lovelace into your classroom

Unless you have powers far beyond those required for teaching, you won't be able to invite Lovelace to your school to talk to your pupils. However, you can do the next best thing by showing them a photo of that letter:

Using artefacts from the past really helps to bring a lesson alive, in my experience. In one school I worked in, I managed to persuade the headteacher to let me get rid of several ancient computers: a suite of 486Zs and a bank of mini computers. However, I kept a 486Z, a 386Z and one of the mini computers. Using them alongside other items, such as 5.25" disks, I set up a mini computing history exhibition at the back of my classroom. The kids found it fascinating.

Another example: when I taught Economics, I brought in a collection of real banknotes from the German hyperinflation of the 1920s. It's one thing being told about inflation; it's quite another handling an actual 100 million mark note and being told it would buy the owner a loaf of bread -- if they were lucky.

I think having real objects, or at least photos of real objects, helps to place the subject in context. Getting back to computing and education technology, we think of "coding" as something new and modern, but to see that somebody thought of it over 100 years ago is quite something.

Useful websites

British LIbrary: letter from Ada Lovelace

The National Computing Museum

Making it possible for students to come face to face with real things from times gone by can have an electrifying effect on them. This is especially so when teaching Computing.